We interviewed old school game tester Robert Zalot about his time at Epyx and in EA’s GOD Squad.

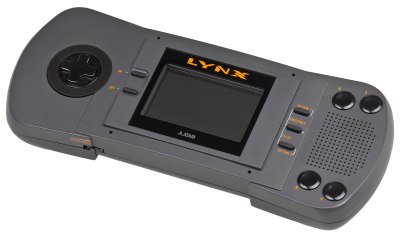

In the summer of 1989, he was unemployed and in search of anything tech-related. When a temp agency called his friend with an offer to “test joysticks” for a secret project in Redwood City, he stepped in, and immediately recognized the location as Epyx’s office in Redwood Shores. What he thought would be monotonous joystick testing turned out to be working with gigantic prototype boards of the Atari Lynx.

He was hired the next day and went on to test Atari Lynx, Sega Genesis, and SNES games through late-night shifts, reporting fresh bugs to programmers each morning. Later, he joined EA’s elite QA group (“GOD Squad”), working across consoles complete with in-house debug hardware, spreadsheets, and pen‑and‑paper tracking, long before modern bug‑tracking systems existed.

His journey began as a temp job and turned into firsthand participation in early handheld console QA, shaping his path in video game history.

How did you end up testing video games?

It was the summer of 1989, and my friend and I were on a break from school. Both of us were unemployed and broke. He applied for temp jobs at agencies all over the (silicon) valley because he had taught himself to code. I had applied at a few temp agencies too, but with no luck. I was into computers, but didn’t consider myself a programmer, so there were far fewer positions I could take, but I wanted to do something in technology. Eventually, my friend got a job as a programmer, but this one temp agency kept calling him and was desperately looking for people to «test joysticks.» He turned them down because he already had a job. Eventually they called him and asked if he knew anybody else that would be interested. He passed my name on to them and I got a call from one of their people.

The recruiter said that they were trying to fill spots «testing joysticks on a top-secret project at an unnamed company» in Redwood City. Also, he asked me if I could work nights… It sounded mind-numbing. I had visions of pressing U,D,L,R,A,B, START all night long at a conveyor belt of game controllers at some factory. I needed work, and the pay was good (for the time – if I remember correctly, it was like $12.50 an hour!) so I said I was interested and the recruiter set up the interview.

Strangely, he drove me to there. That just made it seem even more secret. He didn’t just tell me the time and the address so that I could go to the interview myself, he physically brought me there. I was a little nervous, but it just added to the intrigue I suppose. We finally pulled into the Epyx offices at Redwood Shores [co-incidentally, these exact same offices are where 3DO would end up later] and I recognized ehere we were; because of the company name and logo and from playing their games, but also from «dumpster diving» their trashcans when I was younger to try and get free games! Remember, this was the era of Wargames (the movie) so stuff like that was a thing back then, especially when you grew up right in the middle of it all.

I was relieved that we were at an office building, not an industrial joystick factory, but I still had no idea what I was really going to do there. I interviewed with the testing manager and one of the programmers. Either they were truly desperate, or I convinced them that I understood what bugs were, because the next day the recruiter called me and said that I got the job. When I finally showed up for work, it was better than I could have imagined. I was testing video games, not joyticks, on a brand new gaming system.

Those «top secret joysticks» were actually giant open-board prototypes of the Lynx portable game console (codenamed «Handy») being developed there and eventually released by Atari. Those things covered an entire desk! There were exposed chips and wires and cables everywhere, on a giant circuit board with a tiny screen and an NES controller hanging off the front for us to use. It all ran connected to an Amiga (500 I think?) and it all seemed very complicated at first.

You tested games on the Atari Lynx, Genesis, and SNES. How were the projects run back then? How big were the teams, and how did testing fit into the production lines?

At Epyx the teams were very small, but also we (the testers) didn’t interact with many people. Just the Test Manager and a couple of programmers in the mornings. The dev systems were all in a special access area of the building, and you needed the right badge to get in. Also, we were there in the middle of the night like I mentioned so we just didn’t see a lot of folks. So, I don’t really know the sizes of the teams. We were mostly there by ourselves like ghosts in the middle of the night.

The night shift had us testers showing up at around midnight, then test games all night long. This was so that we would have fresh new bugs waiting for the programmers when they got in at around 9 or 10:00am. There was an incredible time crunch on all the projects, so I was told that it would be more efficient if we staggered our schedules. That, and of course, there were only a handful of dev systems in the entire world at the time, so we couldn’t test if a programmer was working on the dev machine. Really, it was just logistics.

The hours were weird, but we were all a bunch of kids so we shrugged it off. It got interesting when school started back up in the fall though. For a couple of months, my schedule was to test games all night, head to school directly from work to attend classes, go home and do my school work, then take a nap and do it all over again! Fun times.

It worked well though. In the mornings, we would usually meet up with the programmer on a particular game – usually there was one engineer for each game – to go through the bugs. Sometimes, we would need to recreate them on a dev system with all the debug stuff running. That was sometimes stressful. Other times it was just handing off a list of new issues and what was regressed (confirmed as fixed) the night before.

A couple years later at EA, it was a more «regular» schedule, and I tested on the Genesis, SNES, PC… even the 3DO when that was a thing. The QA team at EA was called the GOD Squad – it stood for «Gold or Die» with «Gold» being a reference to the game going «gold master» or final. Which meant that we were there to make sure that the games had no bugs, and that they got through 1st party approvals with no issues. This was a big deal. When you want to publish a game, you have to submit it to the console manufacturer, or «1st party» like Nintendo or Sega, then they would test it to make sure that it was bug-free and good. If a 1st party found an issue and the game got rejected, it was basically your fault because you didn’t find the bug in the first place. This would then impact the release schedule because the company would have to fix that new bug, then re-submit it.

It was actually a lot of pressure, but we also felt a lot of ownership at the time, and worked closely with the Producers and Leads to make sure the standards were high. The goal for the GOD Squad was always to have the first version you submitted to 1st party evaluation be the one that got approved. We had quite a good record too. In fact, a lot of the GOD Squad guys (myself included) were promoted out of testing and up into production.

There was interesting hardware at EA too. There are many accounts online about how EA reverse engineered the Sega Genesis so I won’t go into it here, but the cool thing we ended up with for all that effort were these machines called SPROBES (I think that is an acronym for something! We just called them «Probes»). They were basically full consoles that we (well, the reverse engineering lab) built in-house that let us play the games while they were in development. The Genesis SPROBE is probably the most famous, but there were SNES versions too. They looked like big aluminum pizza boxes – the Sega ones were anodized blue, and the SNES ones were red if I remember correctly. We also used these tall aluminum game cartridges that ran on batteries and let you upload a ROM image onto them. This meant that we didn’t have to go burn new EPROMS every time we needed to test a fix or try out a new build of the game… these were cartridge-based consoles, remember!

The projects were run in a similar way as they are today, except that we were writing issues down on paper note pads instead of entering them in to Jira. Excel was heavily leveraged too as there wasn’t really anything else at the time. Usually there was a «lead» tester from the GOD Squad designated for each game, and they would liaise with the team Producers to figure out what needed to be done. The Lead would guide the rest of the testers, compile and deliver the bug reports, coordinate the game builds back to the testers, assign regression testing… they were basically the glue between the production team and the testing team.

Was all the testing done manually, or was some automation involved?

Back then, the only thing automated was the «turbo button» on your controller! It was all human hands – just body count and brute force. There were VCRs around at EA, though not that many. If you were lucky, you had one at your desk and you were recording when you found a bug. For the most part though, if you saw anything, you wrote it down (yes, pen and paper) and then tried your best to make it happen again. If you could only make it happen that one time, the bug was almost invalid, so you really tried your best to recreate it. It was like being a detective in a way because you needed to figure out what caused it, then confirm it by reproducing it.

If it was late in the testing cycle and the game was going to be manufactured soon, there was often a crunch to make sure that all of the bugs were closed/fixed. If you found something bad at that stage, then you might be assigned to a programmer’s office, playing on a debug system trying to recreate the bug for them live. This could take hours, even multiple days. Yes, you were literally «playing games for a living,» but that could mean that you were playing the same section of the same level of the same game for an entire week, all under the pressure to perform! Okay, it was still fun though.

Did you have to follow a test plan/strategy, or did you just play the games?

Sometimes there was a full game design to use to make the test plan from. If not, then we would do our best to know what the game was supposed to do so that we could tell when it didn’t. The games were pretty simple back then, so it wasn’t hard, but there were still debates. They were mostly about UI and button mappings and things like that… the tester’s secret weapon was to just report it as a bug. If you wanted «jump» to be on (A) instead of (X), you could make sure the producer saw it by putting it into the bug report as a bug. Most of the places I worked though were always open to discussion, so you could just talk to the Producer or Designer and tell them why you thought it should be different.

Depending on what phase you were in, you did different things. During development when a new build came in, you would test whatever was new in that build; maybe a feature got added, or a new level or something. You would bang on that to make sure it worked properly and didn’t break anything else. Usually in this phase, there were debug commands so you could be invincible or give yourself ammo or whatever, and level select codes so that you could jump around easily.

Later on, when you were shooting for the Gold Master (GM), you would play a «release candidate» build. That meant that if no bugs were found, it was going to be the version that shipped – so those secret menus and key commands were (usually) all taken out. It was just you versus the game at that point, so testing got a lot harder. The test plan during GM was usually to take the new build and start by regressing anything that the engineers said was fixed («claimed fixed») from the previous build. Then also, test against any other important or problematic bugs from previous builds. These might be things that were difficult to fix, or the programmer wasn’t confident about the fix, or just issues that the Producers might be worried about.

You would usually do some form of «bulk» testing too, where you would wrangle as many people as you could find and have them all play the same build for a period of time. This was just to get coverage on the game and to get some fresh eyes on it too. Also, there was something that we did that was called «soak testing» where you would just leave a spare system running the game for days at a time. Then you would check in on it occasionally to see if it was still doing what it was supposed to be doing. Things like just running the title sequence or boot screens, or maybe pausing the game in a specific place, then letting it go for a couple of days (while you did other testing of course!). It might just sound lazy, but we found bugs that way!

If you created manual test cases, how did you track progress?

Progress was typically tracked by the Producers and Lead Testers to make sure that the entire game got the right amount of coverage. That and the regression testing. The games back then were pretty simple, so there weren’t really any test plans or elaborate prep. If a game had, say, tons of stats, or items, or perhaps it was a sports title that tried to emulate the actual (real world) athletes, then you might get a list of those values so that you could make sure that the game was behaving as intended.

What kind of testing tools were used for bug reporting?

I have mentioned some of them, but aside from the unique hardware we really did just write things down on a pad of paper. Again, having a VCR was very helpful back then, but as far as software goes, there wasn’t anything specifically for testing like today. As a Lead Tester I would gather reports from the other testers and track them in a spreadsheet. Later on as a Producer, we moved to home-brewed databases, or something like Filemaker, or used internally built tools. Honestly, some companies I worked for were still using Excel even up into 2005!

Catching duplicate bugs was probably the biggest issue back then. It is still one today, but not as bad as it was when you were compiling the issues by hand.

Okay, we’re nearing the end of the interview. Do you have any final anecdotes to share?

Since you showed NHLPA Hockey, it reminds me of a story:

There was a bug in NHLPA Hockey where if you ever got a breakaway (just you with the puck versus the goalie with no defenders in the way) you could always score. If I remember correctly, you hit Left, Right, Left, really quickly and then took your shot. It confused the goalie somehow, and the shot always went in.

We called the maneuver the «Matulac» after Steve Matulac, the GOD Squad member who found the bug. In fact, he didn’t tell anybody about it for a few days because he was using it to beat everyone in the office! Eventually though, he wrote up the bug, and I am pretty sure it was fixed. Might have to fire up an emulator to double check…

We’d like to thank Robert Zalot for anwering all our questions!

While Spillhistorie.no is a Norwegian website, we have an ever increasing archive of English-language interviews and features that you can find here.