We spoke with the man behind the Psygnosis logo – and so much more!

English artist Roger Dean is a living legend, and his work in the video game industry represent just a small chapter in his extraordinary career. Dean was born in 1944 in Kent, but spent much of his childhood in Greece and Hong Kong. His father was an engineer in the British Army, so the family had to move wherever his work took him. In particular, the years he lived in Hong Kong would later become an important source of inspiration for him.

After returning to England, he studied art, architecture, and furniture design, and it was actually in the latter field that he had his first breakthrough. He designed what he called the Sea Urchin Chair, a predecessor to the famous bean bag chair.

But it was as a visual artist that he truly made his mark. In 1968, he created his first album cover, for the British rock band The Gun, and later became heavily involved with the prog rock bands Yes and Asia. His cover for Asia’s debut album was voted the second-best album cover of all time by readers of Rolling Stone Magazine in 1982, and it was also Dean who designed the very first logo for Richard Branson’s newly established Virgin Records.

It was in the 1980s that Roger Dean first became involved in the video game industry, where he was not only responsible for a number of iconic game covers, but also some of gaming’s most recognizable logos.

When we reached out to Dean to ask if he would like to do an interview with us, we honestly didn’t expect him to respond. And if he did, we assumed it would be just a small handful of questions answered by e-mail. But not only was he interested in talking with us, we ended up having a long and pleasant video call, during which he happily showed us his work and chatted about a variety of topics.

Note that our main focus was on Dean’s work with games, so if you’d like to read more about everything else he’s done, you could, for example, check out this profile interview at We Love Vinyl. You should also visit his website.

In this article, we present an edited version of that conversation, supplemented with a bit of extra information about the topics we discuss.

The Black Onyx and Psygnosis

We start in the mid eighties, which is when Dean first gets involved in the games industry. His first cover artwork was created for The Black Onyx, a game you’ve probably never heard of unless you’re very interested in the history of gaming. Because even though the producer and designer of that game was an American – Henk Rogers, who we’ll talk more about later – the game was only released in Japan. While it isn’t a famous game, it is an early example of a role-playing game developed in Japan, and it would help influence how Japanese developers approached the genre.

For European gamers, it’s probably Dean’s other contract that proved the most memorable. When the British publisher Psygnosis was formed in 1984, they reached out to Roger Dean to create their logo. This would mark the start of a long lasting relationship which would shape much of the visual identity of the well remembered publisher.

JF: How did you get involved with the games industry? I know that your first work was on The Black Onyx …

RD: That’s right! Well, Henk Rogers, who now publishes Tetris, sought me out – though this was before he got the rights to Tetris. He was aware of my work in music. So he knew my music and my books, and of course my album covers. He contacted me through my publishing company, and came to visit.

JF: But that game only came out in Japan?

RD: That’s correct, yes.

But about the same time I met Henk, I also met Jonathan Ellis of Psygnosis. I had met with Imagine Software before – two of the people from Imagine formed Psygnosis with Jonathan Ellis – and I did a whole bunch of Psygnosis stuff.

JF: They contacted you? They’d seen your artwork already?

RD: Yes, they contacted me. They’d certainly seen the books. We sold enormous amounts of posters and books back then. During the seventies, my posters, books, calendars etcetera sold about 65 million copies, and by the mid eighties we’d passed a hundred million sales. So it was out there, you know. Much more than today.

JF: The owl logo, was that your idea?

RD: Yeah, sure. That was my job. They gave me an idea about the kind of name that they wanted, so even the name was partly mine. Both the name and the owl… they were very clear about what they wanted, but they didn’t know visually or even how to put the words together. So the word came to me in the end, and the visuals.

JF: Do you remember how you came up with the idea of putting an owl in there?

RD: What can I say? *laughs*

JF: Did you see or play the games before you did the covers?

RD: That’s not how it worked. It was the same with the music. Very often I had to finish the covers long before the games were done, and the content of the games was as much influenced by the cover as the cover was by the content.

In fact, I would say that the cover was influenced by them describing what they wanted to do for the game, and then me visualizing it. And then they would reproduce that to some degree themselves in the games.

HAJ: So they just said: This is what we are thinking, and then you started working?

RD: They described the game, usually in much more extravagant terms than what the reality was. They would say they were making an interective movie, and I’d say «wow!». And when I saw it, there would be these little matchstick figures…

JF: What was the process like?

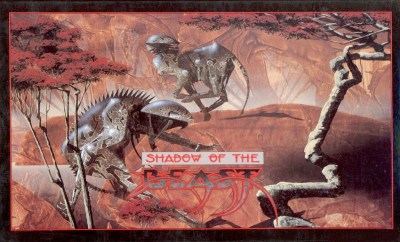

RD: Well, it was very different from the work I was used to doing, so from that point of view it was good fun for me. Like going in another direction, I enjoyed that a lot. Especially the designs I did for The Shadow of the Beast, they were very different from any album covers I’d made.

JF: Did you ever work on actual game [design] for them?

RD: No, I remember when we did a game called Barbarian. The developers got very excited and asked me what I thought of their dragon. And I said, «what dragon?» Because I’d put a dragon on the box, and they’d then put my dragon in the game. And I said, «oh, you have to show me.» And they said, «it’s at the end of the first level, you haven’t gotten beyond the first level?» And I said «noo… I haven’t even started the first level!»

JF: Did they ever come back to you and ask you to redo something?

RD: Not really. Maybe on one occation only. I can’t even remember what it was, but I did the lettering for it, and I found them another artist. In the end, that was a turning point for me, because they were already producing more games than I could possibly manage. So I would end up doing logos, but getting other artists to do the art.

JF: Yeah, I see some of your covers are listed as a collaboration with you and Tim White.

RD: Tim White, yes. There was a number of artists in it. Chris Voss, I think. Peter Jones, maybe. Yeah. There was a few other artists who did covers.

JF: So you did the logos, and they did the paintings?

RD: They did the painting, yes.

JF: Was there a community of artists who did covers?

RD: Well, I knew the artist because I had published the books, and that was in very recent history. You know, within ten years of when we had the publishing company.

JF: I love all the covers you did for Psygnosis. Unfortunately, I don’t own so many, only Terrorpods I think. You did the logo there, I think?

RD: Terrorpods is interesting because I did the drawings for that. The painting was done by Tim White, but it was my drawing. I drew the machine.

JF: It’s one of my favorite covers.

RD: Yeah, it’s pretty good, I like it.

JF: There was also some re-use of older album covers. Did you help facilitate that?

RD: No, it’s the other way around. There were game ideas that became album covers. So game covers that became albums. Barbarian without the barbarian became a cover for a solo album by Steve Howe [from Yes], for instance.

JF: Ah, I see.

RD: The rule that I have is that there can be no confusion. So I never use a painting for one album cover on another. That would not be good. But if it was a totally different thing the rules and the licensing arrangements allowed me to do that.

JF: So you made sure of that going into the projects?

RD: From the very beginning, yes. I kept all the rights.

The evolution of game covers

We asked Roger Dean whether he ever received the finished game boxes he had worked on, and not only did get the boxes – he still has them! He then suggested showing us a few, and returned shortly afterward with the boxes for Shadow of the Beast I and II. Two large cardboard boxes with cover art that is both stunning and unique.

This led to a conversation about how game boxes have evolved over the years, and Dean’s thoughts on the subject.

JF: Where did that [SotB] style come from?

RD: I was very interested in mechanical things. So when I was a student, a lot of my work was about ideas for machinery. So Shadow of the Beast was natural, a very easy connection, and it was good fun.

JF: Those boxes are really unusual.

RD: Well, of course. There are no boxes at all today, are there.

JF: No… I was thinking about that because those big old boxes, they were almost like the the old records, compared to what came later…

RD: Yeah, and these are floppy disks inside. One also besides the floppy disks, I think it had a cassette, and a t-shirt. So it, so it had a book of instructions, floppy disk, cassette and t-shirt.

JF: Yeah. You don’t get that today.

RD: No. And the t-shirt was kind of weird because you couldn’t choose the size, right?

JF: Oh, well, it could be a gift for someone, if it didn’t fit…

RD: It would have had to be. Yeah. *laughs*

JF: But what I was getting at … I assume you’ve seen how game boxes just shrunk and became smaller and smaller, and now we don’t even have them. How do you feel about that?

RD: Well, I don’t know. It’s the same problem, of course, with music. And what happened was that for a very short period of time, music made the perfect gift. You know, a 12 inch vinyl, it looked like and felt like something you would both like to give and receive. And that concept of the gift was really strong.

You know, back when the vinyl was normal, getting a record for your birthday or Christmas was a big deal. And a big deal to give because they were relatively expensive. They weren’t even affordable by young people until quite a few years after they were invented. But it was a big deal, that gift idea. When it first went to CD, the record companies destroyed the idea of a gift because they stripped out a lot of what made it special.

I mean, one of Yes’s biggest albums in terms of its impact and iconography was Close to the Edge. And when it came out in vinyl, the cover had the new logo, but the painting was inside. When it came out on CD, there was no painting, it was just a folded sheet of paper inside. It was black and white, no image. And I thought, you know, this is treating the customers with so little respect. It was just amazing.

And as the industry went into decline, shortly after that, you could see, there was no respect. No respect for the music, for the bands and for the fans. It was their own fault that they were in trouble. The only country where the quality was persistent was Japan. Their CDs were always beautiful. In the West? They were rubbish.

JF: Would you say the same was true for games?

RD: It wasn’t really the size, it was the complete lack of care that really troubled me enormously. I quite like the small versions [of records] that came out in Japan because they were like a kind of bonsai, but everything was there. All the art was there. In fact, Japan had the bonus of having the translation, so you got more than the basic thing. It was good.

HAJ: Do you follow modern video game art?

RD: No, I don’t really. People show me stuff and I go, «wow, that’s pretty cool.» But I don’t go out of my way to follow it.

Tetris, and The Black Onyx part two

Few games – if any – are more famous than Tetris. We won’t go into the history of this addictive puzzle game; you’ve probably heard it before. But it was the aforementioned Henk Rogers who ended up securing the rights to the game, and he also founded The Tetris Company together with the original Tetris creator Alexey Pajitnov. When the time came to create an official Tetris logo in 1997, Roger Dean was the one they contacted.

This, however, was not the only collaboration between Dean and Rogers. The other was an ambitious sequel to The Black Onyx that was sadly cancelled before completion. Based on what Dean tells us below, it sounds like a really ambitious project.

JF: You also worked on Tetris.

RD: I did the Tetris logo. That was just a word, so much less interesting than the Psygnosis logo. But Tetris is a very interesting game…

JF: You knew Henk Rogers, did he always want you to do the logo?

RD: That was more than 25 years ago. Yeah, he he wanted me to do it because there were hundreds of versions out there. Not done by him, but by the various companies that’d license it. And people did pirate versions. Everyone had their own version of Tetris. So he wanted only one version of the logo. If someone had a license, they had to use the authorized logo. It was an attempt to put discipline into it, really.

And then two or three years ago he handed over the management of Tetris to his daughter, Maya, and she changed the logo again. But it’s the same rules, one logo. Although it’s slightly different to mine.

JF: And The Black Onyx?

RD: A much, much, more lavish version of The Black Onyx was due to come out in the States, and I worked on that. It was my job to put together the team that did the content and the packaging, and that included the story, music, landscapes, costumes, everything. I didn’t do it alone, but I put together the team.

JF: This was actual game development?

RD: Yes, this was a full-on role-playing game. A lot of the artwork appears in my book, Dragon’s Dream. But the very big, lavish production never happened, sadly. That was very disappointing. We worked on it for some years, it was good fun.

JF: Do you know why it didn’t happen?

RD: I’m not a hundred percent sure. It was a huge amount of work. It was a real shame that it never happened, because while the technology has moved on, the design would still be valid today. The music is incredible.

HAJ: So is there a chance it could see the light of day?

RD: Heh, yeah, I think Henk Rogers would like to see it published. He owns the game, and I own the artwork. The big game was supposed to be called Onyx.

JF: This was much more advanced than the original?

RD: Way more advanced. Too advanced for it’s time, really. It would have needed 24 CDs for each episode. DVDs arrived in the middle of it, but that would have only divided the number of CDs by three.

JF: Do you remember any game projects that were particularly exciting to work with?

RD: Well, you know what? Onyx, in the end, was the most exciting. Because that was the first time I got really hands on with the content.

And as I said, it’s still never seen the light of day. It is very interesting, because two weeks ago I had a visit from Henk Rogers. He’s doing a book called The Perfect Game about Tetris, and he’s doing an audio book. And in that he talks about different projects, including Black Onyx. For Black Onyx, he used some of the music that we created for the project, and it was really good by any standards. It was a great piece of music, not a great piece of game music, but a great piece of music. Even the music should be published. It hasn’t been, but it should be.

HAJ: Who did that music?

RD: Well, we did it in collaboration with two people called Youth and Jaz. Jaz Coleman was orchestral minded, but he was also a singer for a band called Killing Joke. So he had his rock and roll credentials. But he worked with Prague Symphony Orchestra and things like that. Youth (Martin Glover) was very much into electronic music. He had a band called The Orb, and he worked with people like Paul McCartney. Oh, he did all kinds of stuff. But his big interest was electronic music at the time.

Between them, one producing, one arranging, they made a lovely soundtrack. And it had people like Steve Howe from Yes performing on it.

HAJ: Is there a chance that we will hear this music in the future?

RD: Well, I think yes, because we were all listening to it at least two weeks ago, and that’s exactly what everyone was saying. This music has got to be available. It’s got to be out there.

HAJ: I really want to play this game now … but but the artwork for this game will be out in your next book or calendar?

RD: Some of it will, but it’s in my book, Dragon’s Dream, which was published in 2008.

JF: Was it ever possible to actually play the game – did it get that far into development?

RD: No. Henk would probably tell me I’m wrong, but I’m not even sure gameplay was ever fully developed. The overall concept had to be because we couldn’t structure what we did without that, but we were filling in a lot of gaps. Too many gaps.

I mean, we did a lot of things which were done for the first time. At the time, I studied kendo, which is Japanese martial art with the sword. And my sensei had studied medieval European sword and pole arm spear techniques. For the sword fighting, it was broken up into kata, which is attack, defend, counterattack – sequences that were from real techniques. In a fight you could put it together and it looks so amazingly convincing, and you could watch it from any angle. And we we recorded it in motion capture. So it was very realistic. And it was not just because the motion capture is realistic, but because these were genuine sword techniques.

JF: I know The Tetris Company worked with another company [Digital Eclipse] for an «interactive museum» about Tetris, so I was wondering if something could maybe be saved and published in a similar way?

RD: Well, there is something which is possible. We developed a process that Henk called Track and Field. Track was when the characters followed a specific route, and Field was when they could wander wherever you liked. They couldn’t wander over the whole world because they’d get lost and it would be boring. You had to have a mechanism to bring them back, but you needed them to follow a path.

So you could do it like a movie where there was a sequence that was completely constructed. You could watch it from different angles, but you it was a complete construction, but then you could break off into a game. If for instance it was like Lord of the Rings, they could be climbing the mountain path, but when they’re in the dragon’s lair, then they’d come into the field – the game aspect, where they can wander wherever they want. But once they’re out again, they’re back on the track.

So there’s bits when you can just watch it, it looks great, and then there’s bits when you’re frantically interactive.

HAJ: Did you work on any other interesting projects like this?

RD: Before I met either Henk or Jonathan Ellis, we worked on an idea for doing a project called Taitan, which was an arcade game [cabinet]. We said we were going to manufacture the machines ourselves, and talked to Taito Electronics about licensing the motherboards from them. But instead, they decided to buy out our business, so that’s how that went.

Henk Rogers also got involved with a virtual reality project with us. He was the first who saw this, and he invested in it. We built maybe a dozen prototypes. But again, we were too far ahead of the technology. Mitsubishi supplied the monitors … they were the size of a small car. We had to cut great chunks out of the pods we were making. They were very elegant, but we had to cut massive amounts out of them just to fit in the monitors. They were bigger behind than the screen.

JF: How do you view your game art compared to the rest of the work that you’ve done?

RD: In many ways, it was like returning to roots for me because I never did do fine art at college. I did Canterbury College of Art for four years, Royal College for three. My focus was on architecture. You know, the I studied basically what kind of spaces made us feel good, what kind of spaces made us feel uncomfortable. And my view is very strongly that modern architecture is not good for us. There should have been a better way.

This is what I’m very interested in and focused on now. We’re looking to build a visitor center and museum.

HAJ: Where?

RD: We’re looking at two sites. They’ll be different. One is in England, near here, near where I live, and one is in California.

JF: Thanks a lot for your time. It’s an honor for us.

RD: No, it’s an honor for me. And fun.

HAJ: Thank you for doing this.

RD: Thank you.

Please visit Roger Dean’s website for more of his art.

And visit this page for more of our content in English, including a lot of interviews with games industry people.

A shortened and heavily edited audio version of the interview can be heard here (skip ahead eight minutes to get to the interview part):